Shelf-reading — I’ve never met anyone who loves doing it, but it’s an essential collection management activity. Making sure that every book is in its proper order on the shelf ensures that patrons can access the materials libraries purchase for their use. If the catalog directs a patron to the book she wants on so-and-so shelf in such-and-such order and it’s not actually there? UGH. It makes everyone cranky, and rightly so.

Shelf-reading (looking at every book on the shelf and putting those that are out of order back into order) is an unenviable but necessary job, so I never mind doing it. I much prefer it to having to let a patron know that the book they want should be on the shelf, but just isn’t.

Added bonus? Every time I read the shelves, I find books I’d like to read. Granted, I find more than I can reasonably read in a lifetime, but now and then I find one that becomes a favorite. It’s how I found both David Levithan and Cormac McCarthy — two very different authors, who’ve written some of my favorite books.

I’ve been reading the fiction shelves at one of my libraries in 30-minute increments in the last month, and I’m halfway through the C authors. Here are a few books the publishing industry isn’t necessarily rushing out to promote that I’m adding to my “To Read” list.

- Between two seas / Carmine Abate ; translated by Antony Shugaar / The photographer Hans Heumann travels to southern Italy in search of the light that has long attracted artists. There he meets Giorgio Bellusci, who dreams of rebuilding the south’s most famous inn. The dark secret behind Giorgio’s obsession will change the course of both men’s lives.

- The king of trees / Ah Cheng ; translated by Bonnie S. McDougall / When the three novellas in The King of Trees were published separately in China in the 1980s, “Ah Cheng fever” spread across the country. Never before had a fiction writer dealt with the Cultural Revolution in such Daoist-Confucian terms, discarding Mao-speak, and mixing both traditional and vernacular elements with an aesthetic that emphasized not the hardships and miseries of those years, but the joys of close, meaningful friendships.

- Cellophane / Marie Arana / Don Victor Sobrevilla, a lovable, eccentric engineer, always dreamed of founding a paper factory in the heart of the Peruvian rain forest, and at the opening of this miraculous novel his dream has come true—until he discovers the recipe for cellophane…A hilarious plague of truth has descended on the once well-behaved Sobrevillas, only the beginning of this brilliantly realized, generous-hearted novel.

- Skylark Farm / Antonia Arslan ; translated by Geoffrey Brock / A beautiful, wrenching debut novel chronicling the life of a family struggling for survival during the Armenian genocide in Turkey, in 1915. Antonia Arslan draws on the story of her own family to tell the story of Skylark Farm. She has transformed the “obscure memories” that are her heritage into a novel as lyrical and poignant as a fable.

- A kind of intimacy / Jenn Ashworth / A darkly comic tale, A Kind of Intimacy is an offbeat and ironic study of misunderstandings. It traces the dark possibilities of best intentions going awry, and gives an unsettling glimpse into a clumsy young woman who has too much in common with the rest of us to be written off as a monster.

- The Yacoubian building / Alaa Al Aswany ; translated by Humphrey Davies / All manner of flawed and fragile humanity reside in the Yacoubian Building, a once-elegant temple of Art Deco splendor now slowly decaying in the smog and bustle of downtown Cairo: a fading aristocrat and self-proclaimed “scientist of women”; a sultry, voluptuous siren; a devout young student, feeling the irresistible pull toward fundamentalism; a newspaper editor helplessly in love with a policeman; a corrupt and corpulent politician, twisting the Koran to justify his desires. These disparate lives careen toward an explosive conclusion.

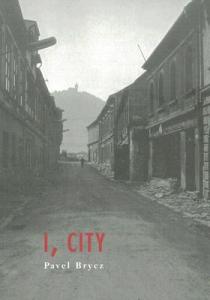

- I, city / Pavel Brycz ; translated by Joshua Cohen & Markéta Hofmeisterová / I, City is a novel about the city of Most in north Bohemia, an ancient city founded on a primeval wetland that was literally relocated to get to the brown coal beneath it. The city is the narrator, telling its own story through its inhabitants, who make their appearances in fleeting, ghost-like vignettes, Joycean epiphanies straight out of a Bohemian Dubliners. As Brycz makes fictional people say factual things and factual people (Kafka, the Pope, the last president of Communist Czechoslovakia, Gustav Husak) say fictional things, post-modernity via Marquez and other so-called Magical Realists makes its almost requisite—though noiseless—appearance.

- My mother never dies : stories / Claire Castillon ; translated by Alison Anderson / Nineteen stunning, disturbing short stories delve into the complex relationship between mothers and daughters. In My Mother Never Dies, the literary provocateur Claire Castillon dissects the darkest aspects of the relationship between mothers and daughters. Stunning, shocking, unflinching, and ultimately tender, My Mother Never Dies forces us to look at the worst and best of mothers and daughters. Like the work of Miranda July and A.M.Homes, Castillon won’t let us avert our gaze from the terrible and true any more than from the beautiful and true— because it all reveals the depth of our need for each other.

- And let the earth tremble at its centers / Gonzalo Celorio ; translated by Dick Gerdes / Professor Juan Manuel Barrientos prefers footsteps to footnotes. Fighting a hangover, he manages to keep his appointment to lead a group of students on a walking lecture among the historic buildings of downtown Mexico City. When the students fail to show up, however, he undertakes a solo tour that includes more cantinas than cathedrals. Unable to resist either alcohol itself or the introspection it inspires, Professor Barrientos muddles his personal past with his historic surroundings, setting up an inevitable conclusion in the very center of Mexico City.

- How to be a good wife / Emma Chapman / Marta and Hector have been married for a long time, through the good and bad. So long, in fact, that Marta finds it difficult to remember her life before Hector. But now, something is changing. Small things seem off. A flash of movement in the corner of her eye, elapsed moments that she can’t recall. Visions of a blonde girl in the darkness that only Marta can see. Perhaps she is starting to remember—or perhaps her mind is playing tricks on her. As Marta’s visions persist and her reality grows more disjointed, it’s unclear if the danger lies in the world around her, or in Marta herself.

- Green mountain, white cloud / François Cheng ; translated by Timothy Bent / In a medieval abbey near Paris, in a room piled high with old Chinese texts, lies a manuscript gathering dust. Though ordinary in appearance, it first captures the eye of the narrator of François Cheng’s novel. Then, once he begins to read, it captures his imagination and his heart. The book dates from the mid-seventeenth century, during the twilight of the Ming Dynasty. Barbarian armies are massing along the Empire’s Northern borders, and a vast and sophisticated civilization — during whose heyday China had begun to emerge from its long isolation and undergone an explosion in the arts equal in its way to Europe’s Renaissance — teeters on the brink of monumental and perhaps catastrophic change. Yet rather than filled with lore of military heroism, or with tales of palace intrigue, or with nostalgic memories of better days, the book tells a simple and very powerful love story.

*attribution: book summaries taken from publisher blurbs via Goodreads; some have been truncated; image of I, City sourced from alibris.